Update!

While we originally planned to spend March - August 2026 in Tarzana, California with Arthur's parents, Igor and Masha, we've revised our plan to go to Denver, Colorado directly instead (where we're renting a condo in the Federal Heights neighborhood). While the tradeoff is an additional 1.32 IQ point hit (for a projected total of 2.7 points), that's still much better than the 4.5 points of going directly back to Bailey. This change is motivated by several factors:

- Having the whole zoo with us is likely to be a bit of an imposition, and we don't want to contribute to the stress of what will already be a big adjustment for everybody.

- Chase will be able to still live with us in Denver in April and May, whereas if we were in California, he would have had to go back to Colorado for those two months to finish out teaching the Spring semester.

- We'll be close to our home in Bailey, so we can make trips up to visit and check on things more easily, as well as pick up any forgotten items. It will also make moving back home in the Fall much easier.

- We'll have better continuity of care with Dax's already-identified pediatrician in Denver, Dr Emily Granath of Partners in Pediatrics.

- It simplifies health plan logistics, since Arthur's Anthem plan only provides non-emergency coverage in Colorado.

- Chase will have better access to climbing opportunities in Colorado than in California.

- It's one fewer move!

Provisional Timeline

December 2025: Arthur drove the zoo (Max, Thor, and Murrby) to Kentucky in early December with a car-load of things we need for everyday life. Later in the month, he drove to Chicago to pick up some baby gear from his sister Emily. Chase followed by plane in late December after finishing teaching the Fall semester. We'll get our short-term rental all prepared for Dax's arrival over Christmas and the New Year.

January - February 2026: We expect Dax to be born in Louisville, and we'll keep him there for a few months to build up his immune system and get settled as a new human being before putting him through the stress of cross-country travel.

March - August 2026: Arthur will fly with Dax to Denver, while Chase drives the car with the zoo. We'll be renting a condo in Federal Heights, to stay at a more moderate elevation before returning home to Bailey. We'll invite family and friends to a local baby shower once we're all settled. Exact end date of our stay in Denver will depend on how Dax is doing with development and acclimation.

March - August 2026: Arthur will fly with Dax to Tarzana, California to stay with his parents,

Igor and Masha. Chase will follow by car with the zoo, stopping in Colorado first for some ice climbing before

continuing on to California. We'll invite family and friends to a California baby

shower once we're all settled.

September - October 2026: We'll pack up once more and transition to Colorado's intermediate

elevations in the 4000-6000-ft range, to give Dax a chance to acclimate to higher elevation more gradually.

Meanwhile, the Cades will have moved out of the main house, and we'll get that space ready for us to move in.

September - November 2026: We'll finally return home to Bailey at 9000 feet, hopefully with a well-adjusted and acclimated Dax, ready to thrive in the high country. We'll start setting up our Montessori schoolroom in earnest.

Science Driving the Plan

The most robust study that we have on this (Wehby's 2012 Living at higher grounds reduces child neurodevelopment: Evidence from South America) quantified the neurodevelopmental impact of relatively hypoxic environments in IQ points. When a child spends his first two years at a certain elevation, we can expect a penalty of ~0.45-0.5 IQ points for every 1000 feet of elevation. 4.5 IQ points seemed like too much of a penalty, and there's nothing mysterious about the biological mechanism here:

- infants do not increase their respiratory rate in response to a relatively hypoxic environment,

- they do not produce more hemoglobin to adapt to elevation the way adults can, and

- the oxygen affinity of their hemoglobin is less robust than that of adults'.

Now, applying the learnings of the study to our context required a few extrapolations and assumptions:

The study involved women who gestated at the studied elevations, whereas Jessie is close to sea level. However, subsequent research suggested that that's actually worse than the study's implication, so ~4.5 IQ points would be a lower bound on the neurodevelopmental penalty. The reason is that women who gestate at higher elevations have physiological adaptations that confer some protection to their infants, and we wouldn't have even that. So we're taking this quite seriously.

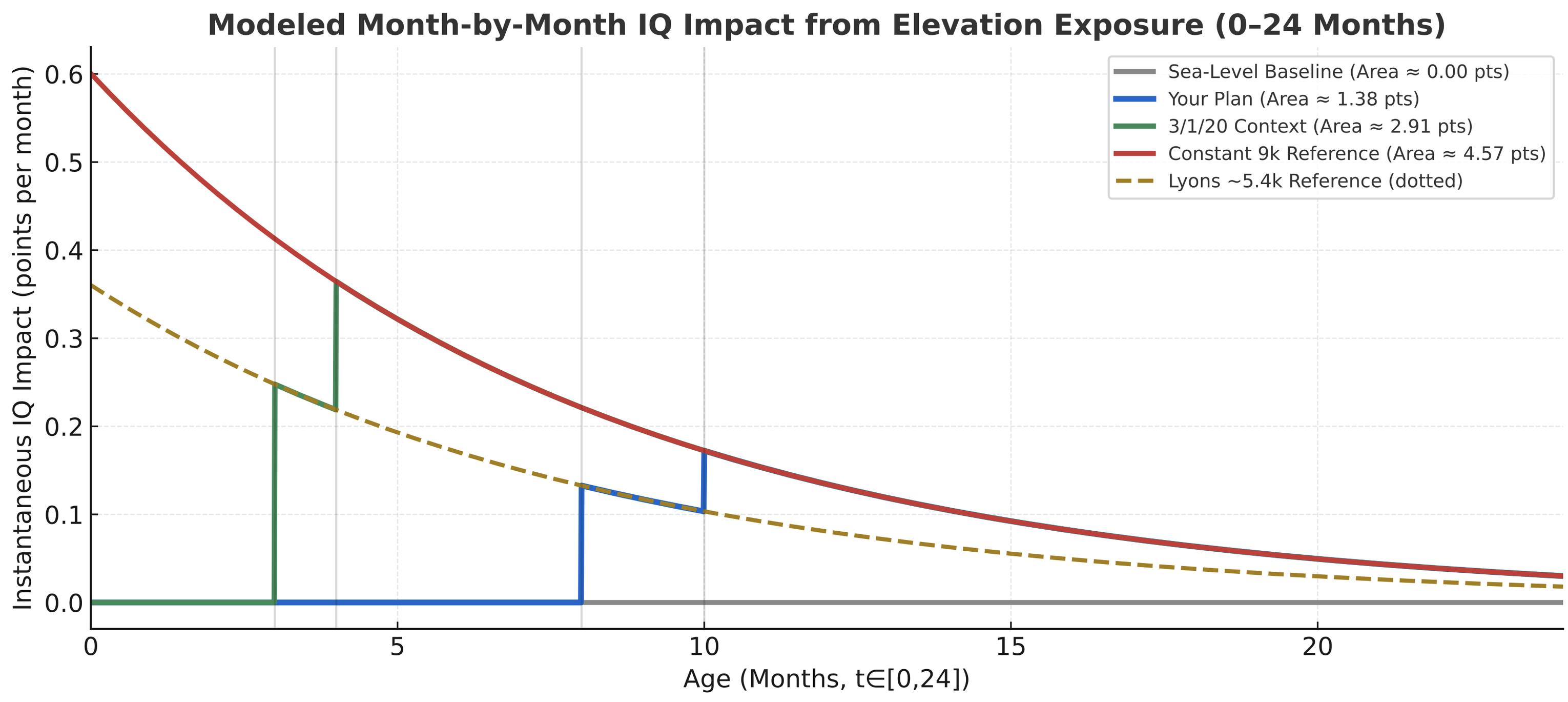

Next, we had to figure out how to model this for different scenarios. Many biological phenomena follow exponential/logarithmic functions, so it's not like there's a constant neurodevelopmental effect for 2 years that then suddenly drops to 0 at 24 months. So, with the help of ChatGPT, we drew a few curves that start with a high effect and taper off to 0 by 24 months, but the area under the curve, representing the IQ point penalty, sums to the effects observed in the study.

Each line represents a different plan, with the IQ penalty being the area under the curve:

- The gray line represents the baseline of staying at sea level for 2 years, which equates to 0 IQ penalty.

- The red line represents the extreme case of going to 9000 feet elevation immediately after birth, which equates to a 4.57 IQ penalty.

- The dotted brown line represents going to ~5k elevation.

- The green line was our original plan of staying at sea level for 3 months, followed by 1 month at ~5k elevation for acclimation, then returning home, ultimately equating to a 2.91 IQ penalty.

- The blue line represents

our finalwhat was going to be our final plan of staying at sea level for 8 months, followed by 2 months at ~5k elevation for acclimation, then returning home, ultimately equating to a 1.38 IQ penalty.

You can see how we're jumping from one line to the next with different shifts in elevation at different times. The equivalent of 1.38 IQ points seems more like a rounding error, and that seems like a tolerable risk, even if it's a lower bound.

Update: Even 2.7 IQ points seems tolerable, given the tradeoffs involved with going to California versus Denver. While it's not as good as 1.38 points, it's still much better than 4.5 points.

Incidentally, we did speak to several pediatricians about this matter; some seemed to think this wasn't a significant issue, and others seemed to think it might be even more serious than we're estimating. In general, though, our concern is that, in our culture's approach to health, most doctors are oriented toward avoiding adverse outcomes that cross clinical thresholds, even in so-called "preventative care". But we're not merely trying to avoid a diagnosis of "developmentally delayed"—we're trying to create the most supportive developmental environment that's reasonably practical. I doubt that many pediatricians, in their clinical experience, have been able to observe 5-IQ-point swings correlating with time spent at elevation, so the most that they can assure us is that most term babies do okay at elevation and that if they seem to struggle, they can get some supplemental oxygen...but they're not terribly concerned with the sort of subtle, subclinical, continuous biological effects of hypoxia on neurodevelopment.

Overthinking It?

Obviously, it's possible for us to stress and agonize so much over trying to optimize every detail that we lose sight of the bigger picture and unwittingly do indirect harm to Dax through setting up a frantic, anxious environment. For those who know him well (or even a little!), Arthur's neuroticism clearly makes him especially susceptible to that failure mode, ironically achieving the opposite of what's intended.

We are trying to be very mindful and aware of these dynamics, and it's part of why we're trying to set ourselves up for success now: When Dax arrives, we'll be too delirious from sleep exhaustion to be able to effectively navigate complex scientific questions, so we're doing as much preparation and planning now, so that when we inevitably get thrown some curveballs, we'll have already considered various options and alternatives and will be able to adapt more nimbly. As they say, "Planning is everything, and plans are nothing.", and so front-loading all this stress will give us our best shot at being able to deal with challenges (and just normal life) with some amount of peace and equanimity!

Do we love the idea of being away from home for 9 months? No. Do we love the idea of moving to Kentucky, then to California, then to another city in Colorado, and then finally home? Obviously not. But we'll do our best to take it all in stride and think of it as a grand adventure, all in service of doing the best we can for Dax. And we're fortunate that we are able to do this—not all parents have the flexibility and life circumstances to support this kind of adventure!